Climate Change Resists Narrative, Yet the Alphabet Prevails (A to Z): Now G!

Article by Elizabeth Kolbert, New Yorker Magazine, 11/28/22

“We are doing freeze-and-thaw tests here in this lab,” Mehrdad Mahoutian said. He pried the lid off a plastic container of the sort usually used to store leftovers. Inside was a gray block about the size of a juice box. It was sitting in a half inch or so of ice-fringed water.

“This is cement-free concrete,” Mahoutian said, indicating the block. “And this is salt water. For eighteen hours, they go into the freezer. And, for six hours, they get melted, basically.”

I managed to find the headquarters of the company named CarbiCrete, in an industrial area of Montreal. Mahoutian, one of the company’s founders, was showing me around the R. & D. facility. Every few minutes, he was interrupted by a very loud rumble. “That’s the blocks being made,” he shouted over the din.

We passed into a second room, where two test walls of cinder block stood perpendicular to each other. Both were equipped with a shower apparatus made from PVC pipe, which was dripping water. A fan blew the water toward the blocks. Mahoutian explained that one test wall had been constructed with ordinary cinder blocks, the other with a new kind of block fabricated by CarbiCrete. The shower arrangement was gauging how the two walls compared in terms of water penetration. “In a few hours, we’ll measure the dampness and do some calculations,” he told me.

Concrete represents one of the world’s most obdurate carbon problems. Its key ingredient, Portland cement, is made by grinding up limestone, adding clay, and heating the mixture to more than two thousand degrees. The process demands a lot of energy, which is usually supplied by burning coal. But, more fundamentally, the issue with cement is its chemistry; heating limestone to the point that it transforms into quicklime unavoidably releases CO2. In 2021, some thirty billion tons of concrete were produced worldwide, almost four tons for every single person on the planet. The associated carbon dioxide emissions accounted for roughly eight per cent of the global total— more than aviation and shipping combined. Producing cement-free concrete, or what is sometimes referred to as green concrete, isn’t sexy, but it’s essential.

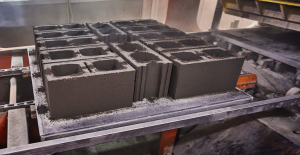

In place of cement, CarbiCrete makes use of a waste product — the slag left over from steel production. It pounds the slag into powder and mixes in crushed rock and water. The resulting slurry, which looks a lot like conventional concrete, can then be molded into blocks or tiles. Gee!

CarbiCrete bills its product, which for the time being is also known as CarbiCrete, not just as carbon-neutral but as carbon-negative. Mahoutian led me to a row of machines that resembled rice cookers. Each one was attached to a cannister of CO2. Inside the machines, little blocks of damp CarbiCrete were reacting with carbon dioxide; instead of releasing the gas, the blocks were soaking it up.

“Please touch,” Mahoutian instructed. The machines were hot. This, he explained, was because the reaction, rather than requiring heat, generated it.

For now, CarbiCrete buys its CO2 from a supplier. The plan, though, is eventually to use carbon dioxide that’s been captured at, say, a power plant or a steel mill.

“What we are doing basically is killing three birds with one stone,” Mahoutian told me. “We are not using cement. We are permanently capturing CO2. And we’re reducing the need for land!lls.” As I was getting ready to leave, Mahoutian asked if I wanted a CarbiCrete tile or cinder block to bring home with me. I thought for a while and then decided to take both. Gee!